Circular Steps Forward: Civic Design Beyond Dialogue

Catalyzing Grassroots Energy into Lasting Impact

ABSTRACT

This article explores how professionals and institutions can spark and manage “collective intelligence” in specific geographic areas—a practice known as Civic Design (Di Siena, 2015). Civic Design focuses on using collaboration and partnership across government, business, and nonprofit sectors to help local people transform their shared spaces (Peña-López, 2019).

Civic Design aims to strengthen a community’s ability to connect and involve diverse groups in processes that improve their environment.

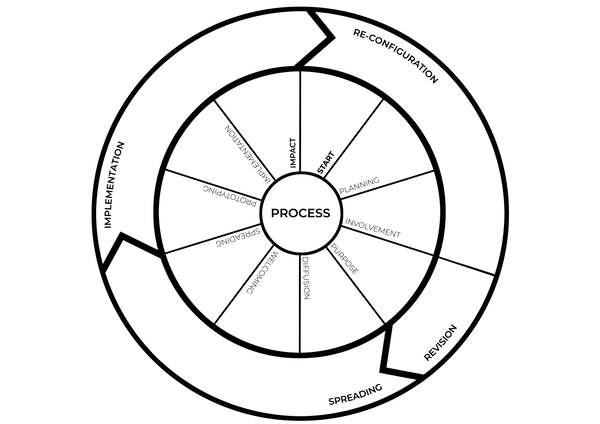

Here, I introduce the “Circular Process” tool, which lays out the key steps and interactions needed to activate collective intelligence. A case study demonstrates how this model can help bring together large groups of local stakeholders and align their efforts with government goals and community needs.

CONTEXT

We live in an era when networks let people collaborate in new ways, creating frameworks that do not neatly fit past definitions (Castells, 2010). Collective intelligence involves blending new capacities for communication and community organizing so that people, in tandem with public, private, or third-sector organizations, can tackle shared goals (Peña-López, 2019).

Yet, many stakeholders are unfamiliar with working cooperatively (Chautón, Di Siena, 2019), meaning we need fresh approaches. My goal is to connect insights from academia, professional practice, and civic activism, as Corsin (2017) describes. Academia is increasingly recognizing grassroots experiments that encourage citizen involvement outside traditional institutions (Lafuente, Estalella, Corsín, 2012). Meanwhile, civic activists appreciate how professional “practitioners” can bring expertise to institutions (Corsin, 2017).

Examples of forward-thinking public agencies and programs—like those described in Abrir instituciones desde dentro [Hacking Inside Black Book] from the LAAAB in Aragón—show how opening institutions to citizens and other local players can foster inclusive, collaborative processes that generate concrete results.

HYPOTHESIS

A new practice called Civic Design is drawing professional attention despite little formal research. It shifts design thinking away from producing one-off products and toward guiding group-based methods, engaging local people in finding solutions to local issues.

Inspired by research such as Buchanan, Amatullo, and Staszowski’s work in New York City, I propose a framework to highlight the core actions and patterns that launch these collective intelligence efforts.

I show how the framework carries us from a locally recognized challenge to a final proposal built through collective, multi-actor, and interdisciplinary practices—highlighting the worth of Civic Design.

METHODOLOGY

This article is rooted in my doctoral studies in Sustainability and Regeneration at the Technical University of Madrid. I have spent over ten years developing an iterative research method, where each step led to new methods and insights.

On the professional side, I have 15 years of experience with collaborative projects, consistently assessing what did and did not work. I wanted to see if my way of operating could be structured into a clear model.

Eventually, I shaped a methodology that uses both local and global collaboration to transform specific places. This synthesis involved two key tasks:

Identifying a common professional approach from multiple real projects.

Comparing a few case studies that clearly illustrate this approach.

From analyzing those experiences, a consistent pattern emerged. Beyond supporting my main idea, this points to a developing field—Civic Design—that appears in diverse contexts but always manages to trigger what we might call “Situated Collective Intelligence.” You can learn more at http://civicdesignmethod.com, including the Civic Design Method White Paper (Di Siena, 2019).

In this article, I focus on designing processes rather than standalone solutions. I spotlight the “Circular Process for Civic Design,” a tool that helps structure how local stakeholders collaborate to achieve broadly supported outcomes. Through a personal case study, I demonstrate how this approach organizes a complex design process.

CIVIC DESIGN

In my research into collective intelligence projects, I use Civic Design as the central theme. While still underexplored academically, it refers to a collection of strategies that allow communities to work together to tackle challenges in their territories.

Civic Design centers on local residents who share a sense of place. It welcomes multiple disciplines and values localized knowledge. Experts and facilitators contribute professional skills while empowering community members.

Under this approach, the expert’s role is not simply to hand over a completed design but to create a supportive environment in which local actors can collaborate, invent, and co-produce new ideas by way of collective intelligence.

CIRCULAR PROCESS

One outcome of my professional reflection is the “Circular Process” tool, a roadmap that divides a Civic Design project into 10 phases. These phases seek to spark collective intelligence in a specific place.

This sequence is cyclical and flexible, since new ideas and unexpected shifts often emerge from either research or practice. The 10 phases are:

1) BEGINNING – Create the initial team and define the project’s main goals.

2) PLANNING – Research local communities and key stakeholders. Set up stages and objectives.

3) INVOLVEMENT – Welcome and engage local people. Bring on professionals with different expertise, aiming for interdisciplinary and “glocal” perspectives. Foster open, transparent teamwork.

4) PURPOSE – Revisit original aims with the entire group—residents, professionals, and others—and form a shared vision for method and goals.

5) DISSEMINATION – Publicly launch the project through communication channels, social media, or events.

6) WELCOME – Start activities and platforms where newcomers can feel included.

7) DEPLOYMENT – Carry out the planned collaborative workshops, forums, or other tools to boost collective intelligence.

8) PROTOTYPING – Develop trial versions—prototypes—at low cost to see how ideas might function in real life.

9) IMPLEMENTATION – Integrate lessons from prototyping into the final design.

10) IMPACT – Wrap up the cycle and decide on follow-up. If successful, replicate, connect, or scale it.

Next is a practical example of how these steps played out in real life.

CASE STUDY: DREAMHAMAR

Dreamhamar is a project by Ecosistema Urbano, a Madrid-based architecture and urban design firm. It focused on re-envisioning Stortorget Square in Hamar, Norway, starting with a 2010 competition and realized from 2011 to 2012. Dreamhamar was innovative in combining open discussion, workshops, interactive media, and social events to get residents involved in reshaping their own public space.

The project required balancing the local administration’s expectations with broad community input, while also adapting to a new cultural context for the project team.

These 10 phases illustrate how it unfolded:

BEGINNING: They built a multidisciplinary team and put forward a proposal to the city.

PLANNING: They designed a program of outreach and activities to activate the square.

INVOLVEMENT: They brought in local organizations and global networks, emphasizing transparency and collaboration.

PURPOSE: The initial vision was refined in light of local constraints and a shorter timeline.

DISSEMINATION: Communication efforts used a distinctive brand identity and a public event for visibility.

WELCOME: A physical meeting place—called the “Physical Lab”—was set up for anyone interested, including teachers, parents, or curious passersby.

DEPLOYMENT: Workshops, online events, and creative sessions ran parallel, ensuring that those who could not attend in person could still take part digitally.

PROTOTYPING: Temporary interventions tested fresh ideas in the square itself, sparking public feedback.

IMPLEMENTATION: Architects integrated the best insights into a preliminary design.

RESULTS AND IMPACT: After project handover, local political changes led to a partial shift in final construction. Some participatory elements were not fully realized.

CONCLUSIONS

Civic Design involves shaping environments through thoughtful processes rather than imposing solutions from the top. It depends on professionals who facilitate community engagement while leveraging their own expertise.

Success hinges on organizing the process so that local people remain motivated.

Tailoring tools and technologies to the group’s needs is equally important.

By applying the Circular Process model to Dreamhamar, we can better understand how to manage complex, multi-stakeholder projects that tap into local knowledge. In many ways, it is about designing the conditions for collective intelligence.

Though still developing, this approach can benefit from repeated testing and refinement in real contexts. By studying successes like Dreamhamar, we can consolidate best practices and outline guidelines for future territory-based interventions, all aimed at open, inclusive community participation—what we describe as “Situated Collective Intelligence.”

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bauwens, M. (2012). “Blueprint for P2P Society: The Partner State & Ethical Economy.” Shareable. https://www.shareable.net/blueprint-for-p2p-society-the-partner-state-ethical-economy/

Buchanan, C., Amatullo, M., & Staszowski, E. (2019). “Building the Civic Design Field in New York City.” Diseña, 14, 158–183. ISSN 2452-4298. http://revistadisena.uc.cl/index.php/Disena/article/view/165

Castells, M. (2010). The Rise of the Network Society (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

Chautón, A., & Di Siena, D. (2019). “Civic Transitions.” https://medium.com/@civictransitions/civic-transitions-9acbc11c2d6c

Corsin, A. (2017). “Introduction: The Prototype: More than Many and Less than One.” In Socialising Innovation: Key Issues and Perspectives.

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1980). A Thousand Plateaus. Pre-Textos (1988 Spanish ed.).

Desis Network. (2013). Public & Collaborative: Exploring the Intersection of Design, Social Innovation and Public Policy. Ed. Eduardo Staszowski, ISBN: 978-0-615-82598-4. https://www.desisnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/DESIS_PUBLIColab-Book.pdf

Di Siena, D. (2015). “Diseño Cívico.” Unpublished references.

Di Siena, D. (2019). Civic Design Method Whitepaper. http://civicdesignmethod.com

Lafuente, A., Estalella, A., & Corsín, A. (2012). “Laboratorios ciudadanos: infraestructuras para la producción de la ciudad.” In conference proceedings.

Law, J. (1986). “On Power and its Tactics: A View from the Sociology of Science.” The Sociological Review, 34(1): 1–38. Law, J. (1994). Organizing Modernity. Oxford: Blackwell.

Peña-López, I. (2019). “Fomento de la participación democrática no formal e informal: De la democracia de masas a las redes de la democracia.” In Abrir instituciones desde dentro [Hacking Inside Black Book], LAAAB, Gobierno de Aragón, 2019.